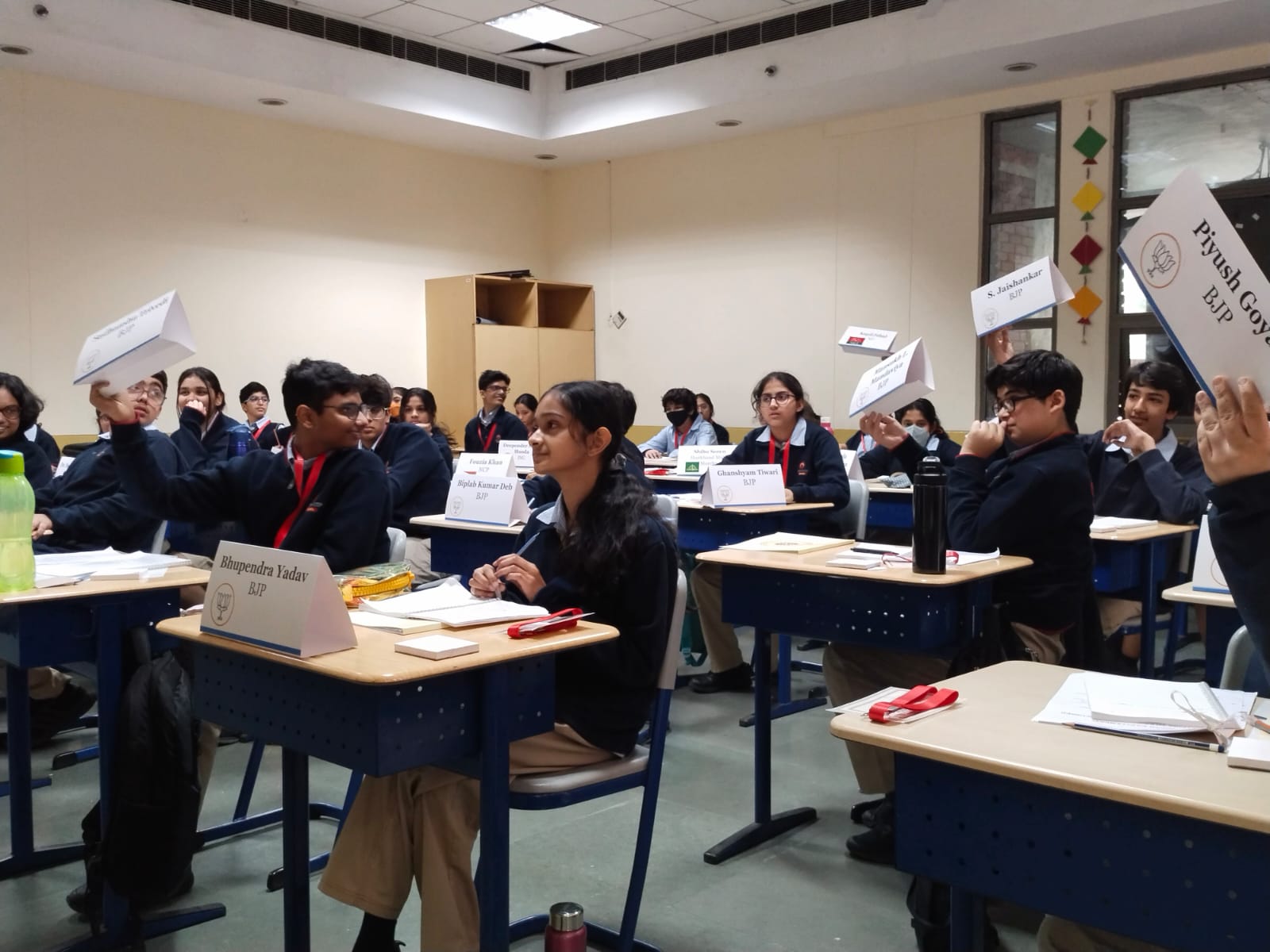

Rajya Sabha

India’s quest for a data protection regime can be traced back to when the idea was first mooted in the Indian Parliament in 2008, when an amendment to the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) was proposed. More than 40 delegates from grade VI-VIII over the course of two will deliberate over the ambit of this law and the necessary amendments that are required as AI become a reality.

What are the limitations placed on Rajya Sabha?

The Constitution of India lays down power of the both houses of the Parliament of India.

For example, Article 84 of the constitution lays down the qualifications needed for a

member to be a parliamentarian. Similarly, the constitution also places some limitations

on the powers of the Parliament and specifically Rajya Sabha.

Another important article of the constitution in this context is the Article 107 of the

constitution of India. The aforesaid article lays down the fact that a bill can originate in

either of the houses of the Parliament with the exception of financial bills and money bills.

The constitution of India lays down that the money bills and financial bills can only

originate in the lower house of the parliament or the Lok Sabha.

The Lok Sabha decides on the bill and then votes on the said bill. The passage of the bill

takes the same to Rajya Sabha. Although the Rajya Sabha has restricted powers over

money bills and financial bills, the upper house can still suggest changes/amendments to

the bill on the table. The Rajya Sabha is only given a 14 day time period to return the bill

to Lok Sabha.

The Rajya Sabha is allowed to either send back the bill with amendments or without

amendments. Regardless, the Lok Sabha will take the final call on the passage of the

amendments. If the Lok Sabha decides to accept the recommendations then the bill is

voted upon again in the lower house and is deemed to have passed by both houses. If the

Lok Sabha decides to reject the amendments then the bill is considered to be passed by

the both houses regardless of the rejection.

In a case where the Rajya Sabha does not return the bill in 14 days then the bill is

considered to be passed by both houses of the parliament either way. So in totality, the

Rajya Sabha has very little say in the matter and the bill will eventually pass at the behest

of Lok Sabha. The role of Rajya Sabha is suggestive.

Article 108 provides for a joint sitting of the two houses of Parliament in certain cases. A

joint sitting can be convened by the president of India when one house has either rejected

a bill passed by the other house, has not taken any action on a bill transmitted to it by the

other house for six months, or has disagreed with the amendments proposed by the Lok

Sabha on a bill passed by it. Considering that the numerical strength of the Lok Sabha is

more than twice that of the Rajya Sabha, the Lok Sabha tends to have a greater influence

in a joint sitting of Parliament. A joint session is chaired by the speaker of the Lok Sabha.

Also, because the joint session is convened by the president on the advice of the

government, which already has a majority in the Lok Sabha, the joint session is usually

convened to get bills passed through a Rajya Sabha in which the government has a

minority.

Joint sessions of Parliament are a rarity, and have been convened three times in the last

71 years, for passage of a specific legislative act, the latest time being in 2002:

● 1961: Dowry Prohibition Act, 1958

● 1978: Banking Services Commission (Repeal) Act, 1977

● 2002: Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002

Lastly, in terms of limitations, the Rajya Sabha does not have the authority to bring a no

confidence motion to the floor. Only the Lok Sabha can bring a no confidence motion to

the floor of the parliament.

Agenda for the session of Rajya Sabha that we are simulating is Reviewing and

discussing the passage of the Personal Data protection Bill, 2019

Background of the Data Protection Law in India

India’s quest for a data protection regime can be traced back to when the idea was first

mooted in the Indian Parliament in 2008, when an amendment to the Information

Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) was proposed. The introduction of the new Section 43A

under the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008 (“Amendment”) inter alia put

an obligation on companies to protect all sensitive personal data and information that

they possessed, dealt with or handled in a computer resource by implementing and

maintaining reasonable security practices and procedures. The Amendment also

imposed a penalty for non-compliance. The Amendment was followed by the introduction

of the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and

Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules 2011, which inter alia specify minimum

standards of data protection for sensitive personal data, including requiring companies

to have a privacy policy, to obtain consent when collecting or transferring sensitive

personal data or information, and to inform individuals regarding who the recipients of

such collected data are.

Over the years, various sectoral regulations and rules have also introduced suitable

remedies and preventive mechanisms for data protection. However, a fragmented set of

regulations and the changing trends in technology have exposed India to the loopholes in

the prevailing laws.

The foundation for a single statute legislation for protection of data in India was laid down

in 2017, in the much-celebrated Supreme Court judgement in K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union

of India (“Puttaswamy Judgement''), which recognised ‘privacy’ as intrinsic to the right to

life and liberty, guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution of India, thus making ‘right

to privacy’ a fundamental right. While chiefly dealing with the scope of rights of a citizen

as against the State, the Puttaswamy Judgement also touches upon protections to be

accorded to individuals in the private sphere. The Supreme Court linked the value of

privacy to individual dignity and used long-standing precedence to hold that the State has a positive burden

of maintaining and preserving this dignity. As a result, the Puttaswamy

Judgement is not only the basis of establishing a prohibition against privacy-violative

State action, but also forms a basis for the State’s mandate to regulate private contracts

and private data sharing, in the interest of individual privacy.

This led to the setting up of the Sri Krishna Committee which floated the Draft Personal

Data Protection Bill in 2018. After amending the bill pursuant to industry and stakeholder

feedback, in December 2019, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology

tabled the Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 (“PDPB”) in the Rajya Sabha.

What is the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019?

Owing to concerns raised in relation to data protection in India, a committee was set up

by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. The Committee was chaired

by a retired Supreme Court judge, Mr. B.N. Srikrishna. As per the preamble of the bill as

introduced in the Parliament, the end goal of the bill was to “provide for protection of the

privacy of individuals relating to their personal data, specify the flow and usage of

personal data, create a relationship of trust between persons and entities processing the

personal data, protect the fundamental rights of individuals whose personal data are

processed, to create a framework for organisational and technical measures in processing

of data, laying down norms for social media intermediary, cross-border transfer,

accountability of entities processing personal data, remedies for unauthorised and

harmful processing, and to establish a Data Protection Authority of India for the said

purposes and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”

The bill was needed primarily due to the issues regarding privacy of individuals especially

because of the practices of the various companies. The usage of personal data by the

companies in India was not properly regulated which led to outcry regarding the privacy

of individuals in India.

The Personal Data Protection Bill eventually went to the Joint Committee of the

Parliament which was tasked to examine and discuss the bill, and propose any changes

that it deems necessary. The committee was initially chaired by Meenakshi Lekhi who is

a Member of Parliament for BJP. However, she was replaced by PP Chaudhary as

ministers are not allowed to chair parliamentary committees.

The potential law intended to make a trustworthy relationship between the individuals

and the companies using or processing their data. It was not only intended for telecom

companies but also for social media and related organisations. The bill called for the

creation of a specific authority to be made in order to allow proper determination of

norms related to usage of personal data of individuals.

The draft bill was inspired a lot from the European Union’s General Data Protection

Regulation also known as GDPR. If it would have been translated into law then it would’ve

put the multinational social media companies into proper checks. However, currently

they remain largely unregulated. The bill intends to supersede the Section 43-A of the

Information Technology Act, 2000 by deleting the said provisions in relation to payment

of compensation for failure to protect the data.

What are the important parts of the Bill?

One of the most important features of the bill is the applicability of the proposed law. The

said law will become applicable on government, any Indian and foreign company, private

individuals and any other body incorporated in India. This ensures that all stakeholders

who have access to personal data of the people are covered properly under the proposed

legislation.

A very important feature of the bill in terms of the responsibilities of the companies and

stakeholders is the appointment of a data protection officer within its ranks to ensure

there is a trained professional advising on data related matters. Another addition which

is impressive is the laying down of redressal mechanisms for complainants with these

stakeholders and companies that have access to personal data.

Consent has been made the central feature of this proposed bill by the drafters. The

subject will need to give consent for the company or the relevant stakeholder to process

their personal data. This has put a host of liabilities on the companies and given the

people an extensive protection from data breaches.

However, there is a mention of exceptions in the bill too. The central government has

been given the power to exempt any company or stakeholder from the application of this

proposed legislation in the interest of “sovereignty” and “integrity” of India.

The Chairperson of the committee that was set up by the ministry criticised this addition

to the bill. B.N. Srikrishna opposed the exemption provided under the proposed law. The

retired judge said that this provision could turn India into an Orwelian state. He clarified

that the power to government agencies to access personal data on the pretext of

sovereignty can have dangerous consequences.

While this exemption part remains a concern for a lot of parliamentarians and experts,

penalties have been embedded well in the proposed legislation. There are two tiers of

penalties and that can act as a good deterrent. However, recently the bill has been

withdrawn by the government

Why has the Data Protection Bill been withdrawn?

The government has explained that the bill has been withdrawn due to the large number

of amendments proposed by the Joint Parliamentary committee. Reportedly, the large

number of amendments from the Joint Parliamentary committee has meant that the

parliament needs to conduct an overhaul of the bill and reconsider it.

However, some sections of the society have discussed that the withdrawal has taken place

due to pressure from the lobby of digital business majors and other relevant

stakeholders. They have expressed the concerns regarding the extremist kind regulations

over export of personal data to companies and also pressured to reduce such restrictions.

Meanwhile, civil societies and pressure groups have also called for withdrawal due to the

discretionary provisions prevalent in the current draft of the bill. They are concerned

about misuse from the government and hence want the exemption provisions to be

changed as per recommendations.

he Joint committee of the parliament also suggested inclusion of non personal data in

the scheme of the proposed law and not restrict it to personal data. However, the

inclusion or addition of non personal data in a European GDPR style regulation is not

sensible. This is also one of the reasons why the government felt it is the right thing to

withdraw the bill for fresh deliberations.

Important Links for Reading

4173LS(Pre).p65 (prsindia.org) - Draft of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019

https://prsindia.org/billtrack/prs-products/prs-legislative-brief-3399 - Legislative

Brief for The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019

https://prsindia.org/billtrack/prs-products/prs-bill-summary-3400 - Bill Summary for

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019

Committee Report on Draft Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018_0.pdf (prsindia.org) -

Committee Report of Experts under the Chairmanship of Justice B.N. Srikrishna

What is the new Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022? (indianexpress.com) What

is the new Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022? (indianexpress.com) -

Comparing India’s draft law with other laws across the world

Questions to consider for Rajya Sabha